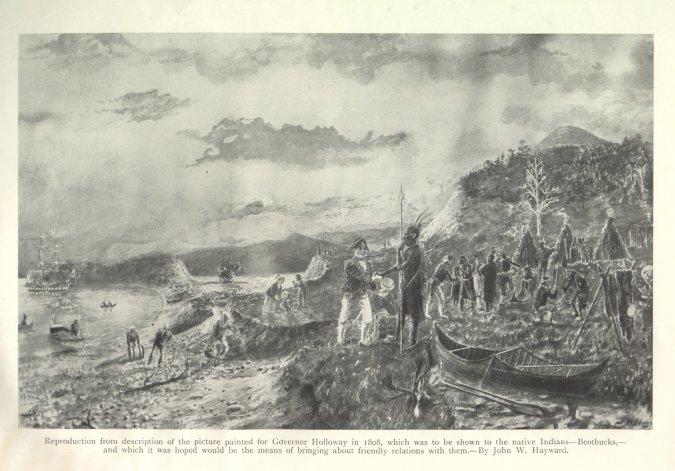

When John Cabot and his crew arrived in Canada in 1497, the playing cards they brought with them were not the first implements of gambling in this land. Thousands of years before the Europeans arrived, Indigenous peoples used gaming sticks and bones in various games of skill and chance. Peoples of the Pacific Northwest, for example, played various versions of a stick game called Slahal—a guessing game, still played today. Such games had many roles in Indigenous heritage—as entertainment, a way to settle disputes, a scared ritual and a means for economic distribution.

Gambling has played different roles around the world and has been viewed in many different ways. Perceptions and attitudes have swung, much like a pendulum, between tolerant and critical, depending on the morals, values and economics of the time. Canada, as a developing nation, has its own story too. Steeped in English tradition, as a British Colony, many attempts at prohibition were influenced by British common law. Gambling plagued the English for many centuries as they made many sporadic attempts aimed at controlling gaming. British law prohibited different forms of gambling at different times and for different reasons. The church, class systems, concerns for national defence have all influenced prohibition.

As people settled in Canada, they brought with them their habits. Gambling became quite popular, even reaching problematic proportions during the 19th century. Different provinces enacted specific laws that concerned their territory which in turn influenced aspects of the Criminal Code of 1892. Games of chance, horse racing and gambling houses were supressed. Later lottery was prohibited. Indigenous cultures were suppressed in many ways including prohibitions against traditional games. Most forms of gambling were prohibited at some point in the century leading up to the enactment of the Canadian Criminal Code.

The way we perceive gambling today is quite different from that of a century ago. Subsequently our laws have followed, although often quite sluggishly, behind the changes in moral ideas within society. The government’s attitude slowly softened toward various types of gambling. In 1900, bingo and raffles were permitted for charitable or religious purposes. And, in 1910, betting on horse racing was allowed. In 1925, games of chance were permitted at fairs and exhibitions. By 1969, the Canadian government had come to appreciate the value of lotteries as a way to generate revenue. Officials amended the law to allow both federal and provincial governments to fund special projects through lottery systems. This was a turning point in Canadian gambling history. The very first lottery was held in 1974 to raise funds for the Olympic Games.

Today, lotteries and other forms of gambling have gained in momentum. Charities, private institutions and governments continue to benefit financially. Indigenous peoples have fought for the right to host gambling on their land and casinos have become a significant source of revenue to help sustain communities. The public has benefitted from projects funded by gambling revenue through social programs. But we still face many of the tensions we did a century ago. We continue to struggle in finding a balance between the desire for revenue and dealing with the consequences of problematic gambling.

To think about – or discuss with a friend

- Imagine the surprise of Jean Cabot, had he carefully observed gambling in Canada—not merely a common practice to pass time but something imbued with spiritual and cultural significance. Where do you think our ideas and beliefs about gambling come from?

- Why might bingo have been legalized in 1900 when other games of chance were not? What factors might have influenced other decisions about legalization?

- Today, gambling revenue adds a significant amount to provincial and federal revenue and in turn supports government services and local communities. It might be viewed as a form of taxation. Is this “taxation” fair? Why or why not?